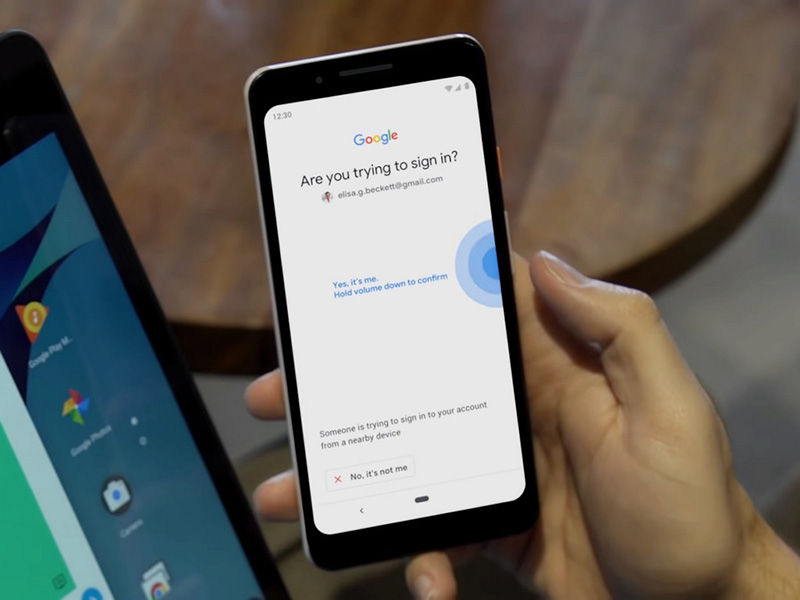

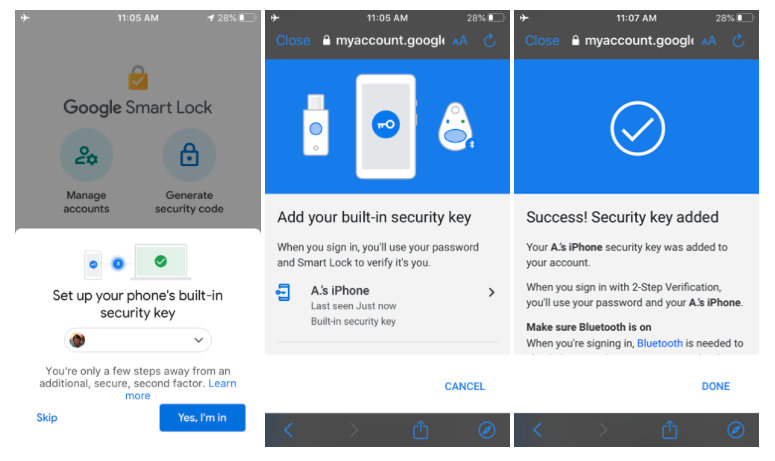

In almost all cases, it shouldn’t be necessary for the user to also-in addition to providing their knowledge factor (such as a password) - re-present their second factor when re-authenticating as they’ve already done that during initial bootstrapping. Optionally, some services might require the user to still periodically verify that it’s the correct user in front of the already recognized device (for example, particularly sensitive and regulated services such as financial services companies). Once this step is completed, it is no longer necessary to require a physical second factor on this device because the presence of the cookie signals to the relying party that this device is to be trusted. Once the user is successfully logged in, trust is conferred from the security key to the device on which the user is logging on, usually by placing a cookie or other token on the device in order for the relying party to “remember” that the user already performed a second factor authenticator on this device. How use case #1 works: Roaming security keys In case #3, FIDO technology helps to determine whether a previously created key is still available on the original device without any proof of who the user is.

In case #2, the problem that FIDO technology tries to solve is re-verifying a user’s identity by unlocking a private key stored on the device.

However, there are some differences, which we break down a bit further below: Security-savvy professionals may interpret the third use case as a special instance of use case #2. This is typically needed in the enterprise.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)